No Stars: A Short History of Industry and Small Business in Port Credit

over Some of the Past Century

In the mid 1970s, Claude, one of my university housemates in Sackville, New Brunswick, planned to travel across Canada at the end of term before he went back home to France. He wanted to visit large cities — Montreal, Toronto, Winnipeg and Vancouver — and get to know the hometowns of his three housemates. I grew up in Port Credit, Ontario, and our other two housemates in Fredericton, New Brunswick, and Kingston, Ontario. Claude’s enthusiasm for visiting his new friends’ places of origin had limits: the smaller centres should have some point of interest. To check on this, Claude had the Michelin Guide to Canada, the authoritative and rather dry French travel publication that offered a brief outline of each town, city and region, and pointed out anything worth visiting, with an emphasis on art and architecture. A system of stars, three being the highest distinction, recognized noteworthy attractions.

Port Credit had no stars. The guide noted that the town, located on the shore of Lake Ontario just west of Toronto at the mouth of the Credit River, was home to two manufacturing and industrial concerns — the St. Lawrence Corn Starch Company and the Texaco Refinery — neither of which, the guide flatly stated, would be of any interest to a tourist. Fredericton and Kingston fared much better; each had a star. Claude opted not to visit Port Credit.

I was miffed. Port Credit, a paradigm of small-town, mid-century North America, was surely worth at least a half-day stopover. Founded in 1889, the Starch Works (as the Corn Starch Company was popularly called) was small-town manufacturing writ large. Raw materials arrived and processed goods departed, first by wagon team, and later by rail and tractor-trailer, all of which sported the Starch Works’ distinctive namemark. Great volumes of food staples were created: laundry and cooking starch, corn oil and that ubiquitous, if often hidden food sweetener, corn syrup. All this starch, oil and glucose syrup was produced in an imposing and sooty number of brick factory buildings with many, many domestically scaled sash windows that inexplicably always seemed to be dark. A forest bordered the factory to the east. Seven times a day, the factory steam whistle would sound throughout the town to let the workers know when to wake-up, start work, have lunch, and so on. All of us in the town orchestrated our day by the whistle.

The Starch Works was managed by successive generations of the Gray family, and in the midst of the Great Depression, rather than lay-off the company’s workers, then president William T. Gray employed his workers to build the Factory Office on Lakeshore Road at Hurontario Street.[fig. 1] The 1930s building is an ornamental brick building with a prominent central doorway with a transom window above filled with their namemark, handlettered in gold leaf. Surrounded by ornamental wrought iron, the lettering would reflect the ambient light and hauntingly glint out at you as you walked by.[fig. 2]The company’s smokestack was a key landmark to mariners on the lake. But the Starch Works' greatest visibility was achieved through their NHL hockey card promotion: from 1943 through 1967, consumers could mail in proof-of-purchase labels to the company and receive black-and-white photo portraits of current players in the league. This highly successful food promotion campaign resulted in “a major sales boost for the company’s products” — particularly to its popular Bee Hive Corn Syrup.(1)

Further west of the Starch Works on Lakeshore Road at Stavebank Road, Texaco purchased an existing oil refinery in 1959. From 1932 on, a succession of owners had maintained a refinery on the waterfront site of a nineteenth-century brickworks.(2) The refinery employed fewer townspeople than the Starch Works and presented a nearly bucolic aspect to passers-by. Row upon row of pristine white oil storage tanks occupied a vast field of trimmed grass; and, each of the tanks sat on its own manicured hillock. Every tank had a reference number ever so neatly painted near the top. This parkland of monoliths sat behind a tall chainlink fence, and in the distance the refinery fires burned high in the air, night and day. From Lakeshore Road, the field of storage tanks’ order and accountability set against the refinery’s distant flames presented a striking if contradictory image.

In the 1920s, European architects such as Erich Mendelsohn and Bruno Taut travelled to Buffalo, New York, to see the pared-down purposefulness of the city’s lakeside grain silos. Industrial buildings such as these held great fascination for the early European modernists, supporting the architects’ dedication to simple geometric forms and monumentality.(3) But by the 1970s, Düsseldorf artists Hilla and Bernd Becher’s documentary photographs of the German industrial landscape had become well known. I’m not entirely certain that oil storage tanks in France familiar to my friend Claude would have differed greatly from the tanks in Port Credit, but as a child I found in the refinery site a kind of reassuring simplicity of purpose. The place was more ideal model than actual thing.

In 1999, Canadian photographer Edward Burtynsky photographed another refinery on Lakeshore Road in nearby Oakville, just west of Port Credit. Burtynsky’s images depict the Oakville Refinery’s intricate network of pipes, ducting and valves as rational, stainless steel order glistening in the midday light. Given Burtynsky’s environmental activism, the artist no doubt intended subtle critique. But his photographs (now in the collection of Oakville Galleries), could well be seen as presenting industry in a utopian manner, much as I perceived the Port Credit facility — sans irony — many years ago.

Most of us have a fond attachment to our hometowns or regions, and often that attachment has some measure of nostalgia and not a great deal of objectivity. Certainly, much of what I valued in Port Credit as a resident would have been lost on a first-time visitor. There was little concern for the production of tourism in Port Credit even into the 70s; there was employment and a satisfied insularity that comes of self-sufficiency. Port Credit was then and will forever be in the shadow of the region’s far greater attraction, Toronto.

Beyond a travel guide’s snapshot view of Port Credit as an industrial centre, the town was defined by numerous other, much smaller, commercial ventures. In 1950, the eastern side of Port Credit beyond the Starch Works and south of the Lakeshore Road was largely residential with only the odd commercial building on the Lakeshore. The two apartment buildings (between Oakwood Avenue North and Woodlawn Avenue on the north side of the Lakeshore) with the beautiful, eccentric concrete entrances in the form of two intertwining tree trunks hadn’t been built yet.[fig. 3 & 4] North of Lakeshore Road was largely fields and woodlots.

In 1950, the Maxted Pharmacy building on the southwest corner of Lakeshore and Hiawatha Parkway was just being built, and Henry’s Hardware (later, and for many years, Ventresca’s Supermarket) on the southeast corner of the same intersection was also under construction. Reg and Mary Marshall had already established Marshall’s Sport and Gift, in the middle of the block bracketed by the Village and Maxted Pharmacies. On the northwest corner of Lakeshore and Briarwood Avenue was the home and office of Doctor Brayley whose name may now be found on the three-story Brayley Building office complex built on that site in the 1960s. There was no commercial development between Cumberland Drive and the St. Lawrence Starch Works to the west at all. Paul Velano’s Flame Steak House, the area’s fine dining mecca throughout the 1960s and 70s, was years away.

In 1950, my father opened up a jewellery and watch repair business, some two and a half blocks east of the Starch Works on the corner of Lakeshore Road and Cumberland Drive. The store was located in the then-newly constructed Village Pharmacy building in a small retail space originally slated to become a barbershop. His business motto was “C. Cliff Armstrong for Watch Repair.” My father’s first name, which he didn’t like to use, was Charles.

My father’s journey to retail and watchmaking in Port Credit mirrored the post-war population shift from the inner city to growing suburban centres. Like many World War II veterans, he left the forces young, married, and found he had no immediately marketable skills. Following up on a childhood passion for building model airplanes, he passed an aptitude test and completed a one-year intensive course in horology (watch repair) offered to veterans at the Gould Street Rehab School in Toronto. Following graduation, he worked for the Toronto department store Simpsons for three years as a watchmaker. He didn’t feel that conditions at Simpsons were overly unpleasant, but described the warehouse on Toronto’s Temperance Street in which he and six other watchmakers worked on a quota basis as being dusty and having windows so grimy you couldn’t see out of them. He dreamed of opening up his own business.

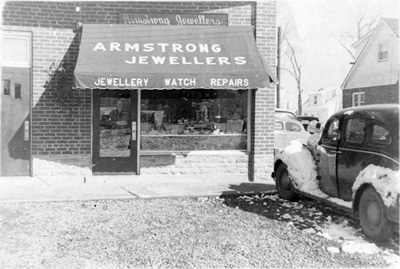

Father first heard of Port Credit’s developing commercial district from a family friend and building inspector for Toronto Township, the regional government that preceded the creation of Mississauga in 1968. On his first visit to Port Credit, Father met Laurie Purdy who was about to open the Village Pharmacy in a newly completed building. (Ron Purdy, Laurie’s son — and longtime community icon and humourist — retired and sold the pharmacy to Joseph Bahrani in 1993.) Armstrong Jewellers opened in October 1950, with a stock of watches, diamonds, jewellery and silverware.[Fig. 5] The focus of the business, however, was watch repair. To celebrate the opening, Father ran a contest to give away a ‘ladies’ and a ‘gents’ watch. He wound the watch up and gave it to the manager of the local Bank of Commerce for safekeeping. Contestants had to predict when the watch would stop — down to the hour, minute and second. A Port Credit businessperson won the contest.[Fig. 6]

By 1952, Armstrong Jewellers had outgrown the modest Cumberland Drive location, and the store moved half a block east into the building that Mel and Gwen Stewart of Stewart’s Hardware had just built. The Stewarts then lived in an apartment above the Village Pharmacy. Initially, Armstrong Jewellers shared its half of the Stewart Building with Able Cleaners (who soon moved several stores east); the jewellery store then expanded to assume the proportions it would keep until 1979. My father’s 1950s renovation of the store included the installation of a custom-built wall and ceiling maple showcases, an aluminium store front with a floor-to-ceiling picture window, a smaller eye-level showcase window, and a store-wide illuminated sign that was ordered at the same time as a matching sign for Stewart’s Hardware. Each week, the windows were cleaned and the floors polished to a high shine.

Living in the ground-floor apartment behind the store, Father ran the business with my mother Lois until the arrival of their first child in 1956 when Do Humphreys was hired as the store’s assistant manager. As the business grew, Armstrong hired Port Credit residents Ethel Brown and Doris Spencer as sales clerks, and another watchmaker was employed. Business was brisk. Every spring and fall Humphreys and Armstrong went to the Toronto Gift Show to order the store’s stock which came to include Bulova watches, Bluebird Diamonds, Royal Doulton figurines, Cornflower glassware, Cross and Olive crystal, Dominion luggage, and tides of costume jewellery displayed on an oval island that occupied the centre of the store. Throughout the store’s 1950s and 60s heyday, many trends in giftware came and went: charm bracelets, serving trays made of cheery fibreglassed cotton prints with the inevitable daisy or happy-face designs, Danish Modern teak monkeys, and handtooled leather encosed lighters. One anniversary happily followed the next.

Father served as an elder of the Port Credit First United Church for 22 years and was a charter member of the Port Credit Rotary Club (1952) which started out meeting in the United church’s auditorium with meals cooked by the church’s Women’s Auxiliary. The club’s first fundraising goal was to equip the operating room in the new South Peel (now Mississauga) Hospital. And, of course, the store sponsored a juniors’ hockey team that first played in the Dixie Arena and later in the newly-built Port Credit Arena.

By the end of the 60s, traffic was slowing in Port Credit retail businesses: Dixie Plaza and then Applewood Plaza had opened, to be followed in the 70s by the Sherway Gardens and Square One indoor malls. But the most severe blow to my father’s store was a 1978 armed robbery. At 10 a.m. one October morning, a man entered the store carrying a knife; he bound and gagged Father, and left him in the back office while calmly serving customers whho arrived during the theft. The bandit took the store’s watches and gemstone jewellery and fled to a car waiting in the alley and driven by an accomplice. The following May, the bandit was apprehended, but by that time he had fenced everything. For security, larger jewellery-store chains hire professional guards; it is seldom that smaller stores are able to afford the prohibitively high cost of theft insurance. Father was not insured; his loss was so great that he was unable to restock the store. In the year immediately following the theft, he feared for his life every time the door opened. Father sold the business in 1979. After a month’s holiday, he once again rented the small store he started out in on Cumberland Drive in 1950. From then until 2000, he concentrated solely on watch repairs.

With the advent of transistorized timepieces, mechanical watch and clock repair has become both boutique skill and dying art. George Brown College in Toronto was the last college to teach watchmaking in Ontario: and it no longer receives enough applicants to run its longstanding horology program. Father’s generation of watchmakers felt it was the trade’s last. In 2000, Armstrong Jewellers celebrated its 50th anniversary — and my father retired. His old store on the Lakeshore is now a bridal boutique.

The St. Lawrence Starch Company was sold in 1989 to Cargill, an American food, agriculture and financial services corporation, and, following the Canada-United States free-trade agreement of early 1989, the company was moved to the US.(4) After 100 years of production, the Starch Works closed in 1990, and most of the factory complex was demolished in 1993 to make way for a relatively low-density, upmarket development of storefront live-work units, condo townhouses, waterfront townhouses and lakeside parkland spread over 16 acres. The development was sensitive and even to a degree green: sightlines were preserved to the waterfront from Lakeshore Road, the factories’ concrete foundation material was crushed and used for new roadbeds, and a good portion of the original forest on the north-east edge of the property was maintained. Project developers Fram Building Group have kept one of the original buildings, the 1930s Factory Office, to serve as its international headquarters.(5) And the Starch Works’ steam whistle — an innocuous structure — is mounted atop a lamppost on the publicly accessible Waterfront Trail that goes through the old factory property.

The Texaco Refinery operated in Port Credit until 1985 at which point the facility was relocated to Nanticoke on Lake Erie. Imperial Oil acquired Texaco’s properties five years later and sought Ministry of the Environment approval to bring in new soil to revitalize the Port Credit brownfield site for reuse. This work was terminated when it became clear that liability for the closure of brownfield sites is not legally settled in Ontario.(6) The sizeable 140-acre property sits vacant and overgrown as Imperial Oil continues to “manage and monitor” the refinery site.(7) [Fig. 7 & 8]

Despite the town’s reluctance, Port Credit was incorporated into the City Mississauga in 1974. Today, even though the town’s retail strip along the Lakeshore still retains its 1950s architectural face, a great deal has changed. Mainstreet retailing has experienced huge competition from strip plazas, mega-malls, and now big box retailers; and social violence has certainly not gone away. In the 1980s and 90s, a number of antique, second-hand shops and bargain shops were established in East Port Credit. There was a venerable precedent for this in Port Credit’s pioneering business in used goods, Ye Olde “X” Shoppe, which was opened in 1952 by Mildred Grebeldinger and later owned by her son Richard, who closed the business in 2002.(8) Most recently, the village is steadily gentrifying with fine restaurants, organic food retailers and art galleries — becoming a bit of a tourist destination. I should let Claude know.

Illustrations:

Fig. 1 - 1930s St. Lawrence Starch Company Factory Office Building, 141 Lakeshore Road East, Port Credit (2009)

Fig. 2 - Front Doorway of 1930s St. Lawrence Starch Company Factory Office Building, 141 Lakeshore Road East, Port Credit (2009)

Fig. 3 - 1950s Apartment Building Entrance, 206 Lakeshore Road East, Port Credit (2009)

Fig. 4 - 1950s Apartment Building Entrance, 212 Lakeshore Road East, Port Credit (2009)

Fig. 5 - Armstrong Jewellers, 225 Lakeshore Road East, Port Credit (1950)

Fig. 6 - Armstrong Jewellers Bulova Watch Give Away, Cliff Armstrong and winner (1952)

Fig. 7 & 8 - Former Texaco Refinery Property, 181 Lakeshore Road West, Port Credit (2009)

Footnotes

(1) Bee Hive Hockey Photos: Obtaining a Photo, <http://www.beehivehockey.com/history_03obtaining.htm>.

(2) Betty Clarkson, The Story of Port Credit (Port Credit, ON: Port Credit Public Library Board, 1967), 175-176.

(3) Kathleen James, Erich Mendelsohn and the Architecture of German Modernism, (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1992).

(4) Clyde H. Farnsworth, “Free-Trade Accord Is Enticing Canadian Companies To U.S.” (The New York Times, Friday, August 9, 1991).

(5) Stephen Weir, “An undiscovered gem: Fram Building Group transformed a demolished starch factory into vibrant live-work community.” (The Toronto Star, July 8, 2006).

(6) G. Peppin, “Real Estate; Can we turn brownfields into fields of gold?” (Mississauga Business Times, November 23, 2005).

(7) “Regent Refinery Not Oldest But Biggest Tax Payer Here.” (Port Credit: The Weekly Special Supplement, July 12, 1961).

(8) Kathleen A. Hicks, Lakeview: Journey from Yesterday, (Mississauga, ON: Mississauga Library System, 2005), 279.